Painting is nothing new for artist Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. He began working with watercolors at the age of 4. Considered a child prodigy at the age of 10, the late Armenian art critic and founder of the world’s first child museum, Henrik Igityan, chose over one hundred of Tigran’s childhood paintings to appear in a 1986 traveling solo exhibition.

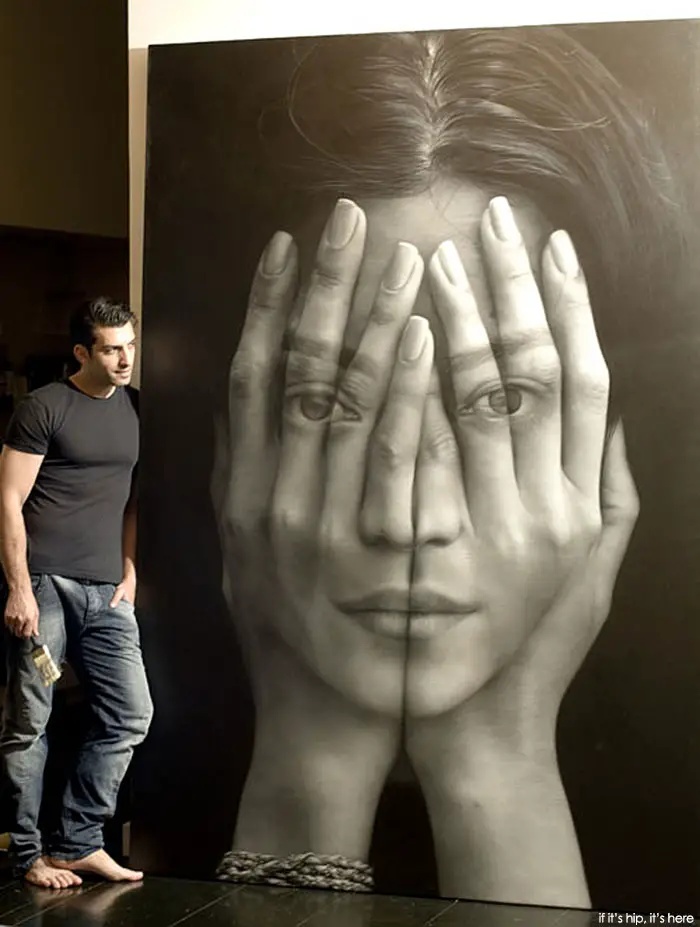

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan Paintings

Tigran went on to be educated at both the Fine Art Academy of Yerevan as well as the ECAV in Switzerland. Now painting in oils, he considers his iconic style to be a combination of a classic technique with a contemporary edge, that is often compared to hyperrealism.

Based in New York, Tigran’s current works are centered on the idea that the world in which we live in is experiencing a “technological renaissance.” His interest lies in capturing the steady flow of information that we are bombarded with through the internet, T.V. and social media within a still moment through his paintings—a moment that forces the viewer to stop and experience the combination of old world techniques with new world ideas.

Described as “absolutely stunning” “haunting” and “incredibly realistic” by various critics and art publications, Tigran’s career is quickly developing into that of a modern art sensation.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan’s Realism By Donald Kuspit

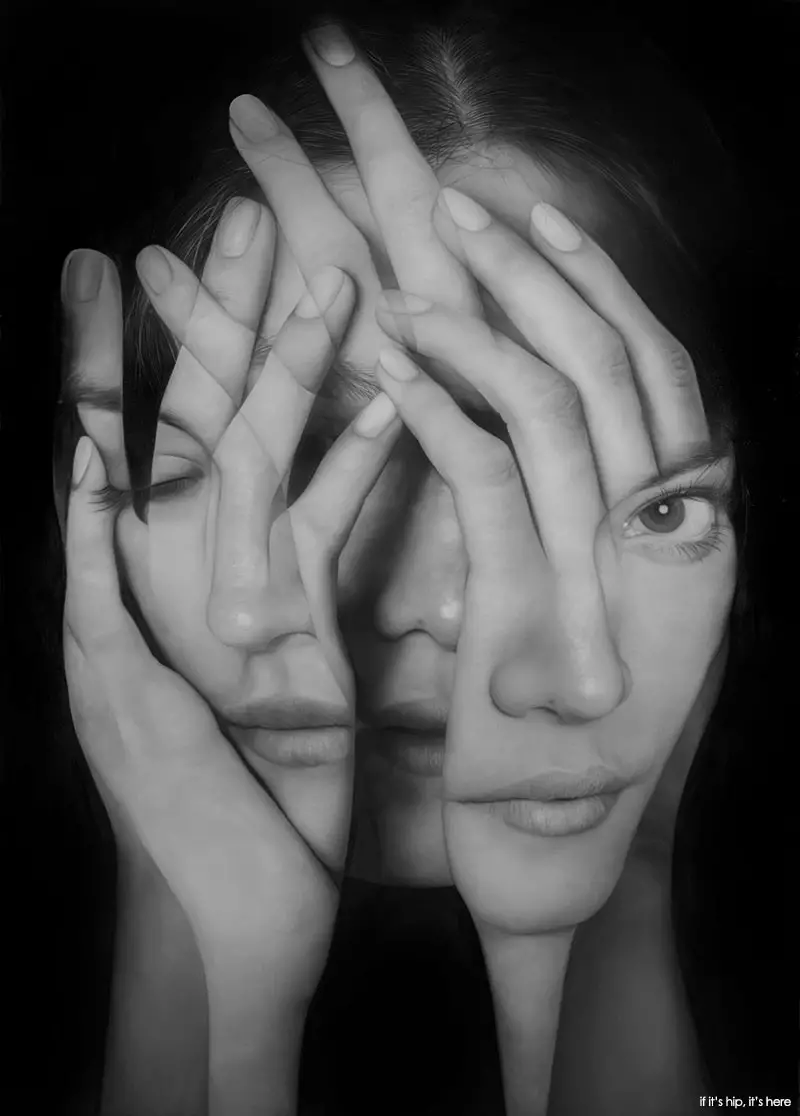

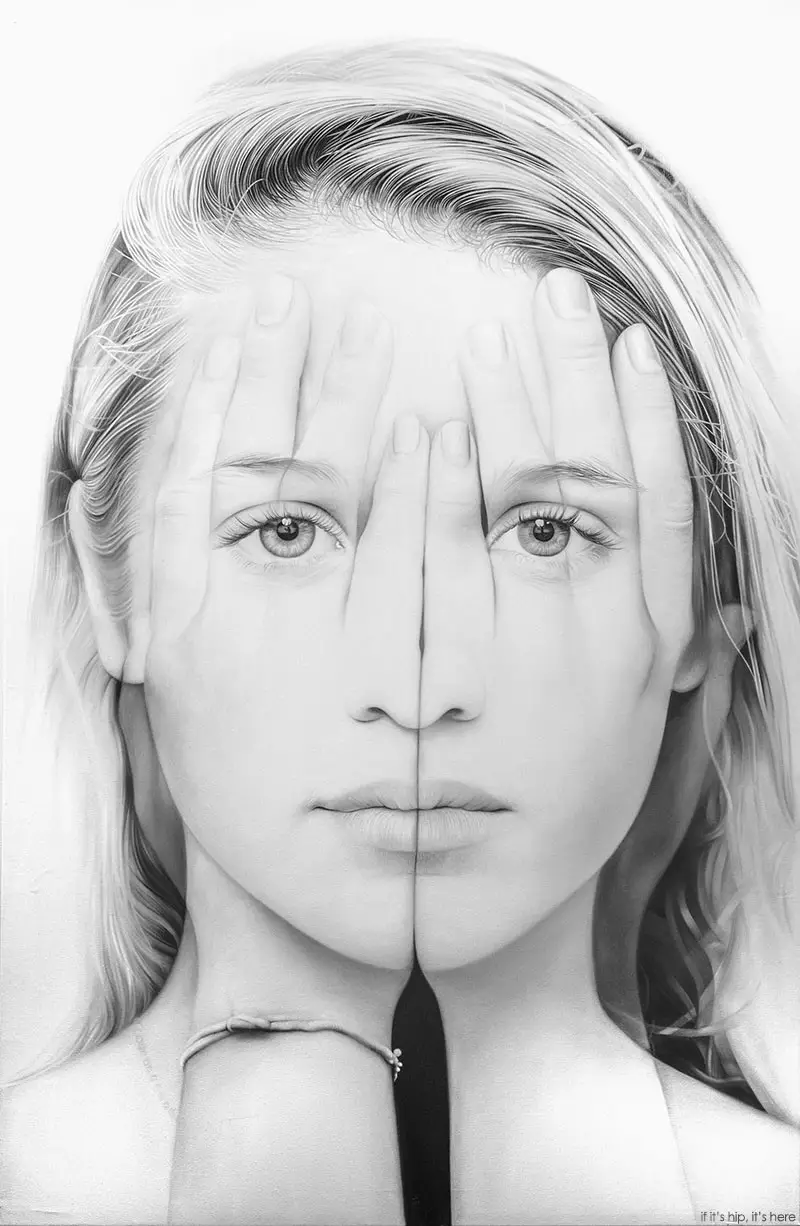

What are we to make of Tigran Tsitoghdzyan’s “Mirrors” — big, bold portraits, confrontationally large, and black and white, like the negative of a photograph, the colors of life enigmatically erased as though in a melancholy underworld? They are clearly masterpieces, but for all the beauty of the female model peculiarly bleak. However well-realized—empirically precise, insistently descriptive—her appearance, she seems peculiarly unreal. The hands that hide her face, yet let her piercing eyes magically see through them, suggest she is a delusion. Ambiguously transparent and opaque, her hands convey the ambivalence built into the artist’s “handling” of her.

The grandeur of Tigran’s paintings suggests that she is a delusion of grandeur—that he is deluded about her grandeur, has made her grander and more mysterious than she is in everyday reality. He has mystified her, so that she becomes the mythical eternal feminine, the embodiment of the mystery that is woman, and with that becomes larger than life, a visionary presence yet still a particular person—Tigran’s wife, the model who is in fact a professional model, posing for photographers. Tigran begins his portraits with a photograph—today taking the place of the preparatory drawing—and ends with a portrait that however photograph-like has the nuanced touches of a refined painting. Carefully constructed of tonal shadows, it has the emotional subtlety that an everyday photograph lacks. Tigran’s portraits lend themselves to reflection, invite lingering contemplation, as a matter-of-fact photograph rarely does. I think this is because each of his portraits, however labor intensive, have the quality of a “primary delusion, i.e., one that arises as an immediate experience, out of the blue, with no external or objective cause or explanation, but nonetheless with a strong feeling of conviction”. Out of the blue, in Tigran’s portraits out of the black, that is, the haunting female face arises out of the unconscious depths however much it is heightened by consciousness. Tigran’s female face is always yonder, at an immense distance, symbolized by its intimidating immensity, however close and impinging it may be. It is a transfixing, perversely sublime spectacle that the spectator only dare view in a mirror–see through a glass darkly, as it were—the way Perseus saw the Medusa’s face reflected in the mirror of his shield, so that he would not be petrified by its stare.

Writing about portraiture, Dostoievski said: “The painter seeks the moment when the model looks most like himself. The portraitist’s gift lies in the ability to spot this moment and hang on to it”. When does this special moment of seeing, this so-called “pregnant moment” of perception, a sudden moment of unusual intimacy, occur? When does the portraitist feel—imagine—that the female Other looks most like himself, suggesting that the female Other is unconsciously experienced, in emotional reality, as a representation of himself, inseparable from himself, and as such as much an internal object as an external object? When is she personalized into what the psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut calls a selfobject, and as such as necessary to life as oxygen, as Kohut says?

In Tigran’s case, I think it occurs at the moment when he decides to divide her face into symmetrical halves, paying homage to the harmony that makes for its beauty while at the same time recognizing that “there is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion,” as the philosopher Francis Bacon famously said. The splitting of her real face makes it strange and unreal, not to say surreally bizarre—immediately absurd, to refer to André Breton’s idea that the sign of a good surrealist painting is its “immediate absurdity.” (Tigran’s early paintings are blatantly Surrealist; the Mirror paintings are more subtly—insidiously—Surrealist.) The face becomes dream-like and uncanny, unfamiliar and forbidding, even as it becomes more entrancing, hypnotically engaging, like her eyes, staring us down through the veil of her hands. Split in half, the face seems irreparably damaged yet nonetheless remains whole, intact. Much the way a male magician puts the luminous body of his beautiful female assistant in a black box which he then cuts in two, suggesting that he has killed her, and then puts the two halves of the box together and brings her unharmed and alive out of the box—we sigh with relief after the initial shock—showing that it was all a trick, a deceptive illusion, so Tigran puts the luminous face of his beautiful female assistant in the black box of his picture, cutting the face in half even as he shows that the halves hold together.

But Tigran’s divisive act is more devastating than the magician’s act, for it mars her beauty. Again and again, with obsessive regularity, Tigran shows her face cut in two, subverting its beauty: his is not simply an amusing magic act but an act of aggression. The cut also suggests that she is flawed; the proverbial strangeness in beauty is after all a permanent flaw. There is an unexpected fault in her that can suddenly open the way the earth suddenly splits open during an earthquake. She can fall apart at any moment—the moment when she most seems to look like himself, when she is no longer Other however Other she remains. The mirror of his art transforms her into a menacing internal object. Tigran cannot separate himself from her, however much he tries to do so by picturing her. His representation of her incompletely externalizes her even as her absurd appearance gives her unusual presence, confirming her hold on his psyche. He is possessed by her however much he tries to purge her from his being, engrossed in her however strange—oddly grotesque—her doubleness makes her.

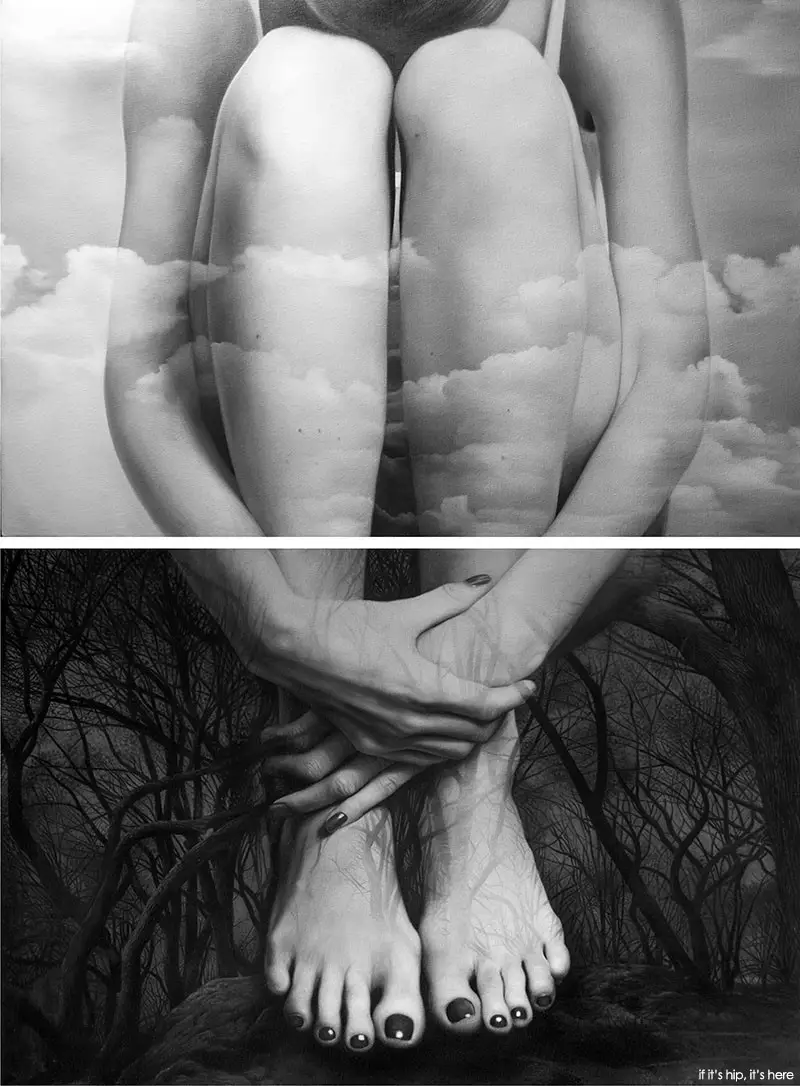

Sometimes Tigran strips her head of its hair, at other times he narrows it, a streamlining that makes the head oddly skull-like, however clearly alive the figure is. In one work her head rests on her left arm, which rests on a table together with her left arm, with her image mirrored in the table, compounding the melancholy her pose suggests. In a similar work we see her from above and behind, her luminous head and hands resting on the black table, with its mirror-like smoothness. In a particularly remarkable work— an ingeniously allegorical diptych—Tigran divides her body in half. In the morbidly dark lower half her hands and feet, the former with painted fingernails, the latter with painted toenails, suggesting her sexual appeal not to say erotic intensity, appear in a black tangle of dead trees, suggestive of the dark forest in which Dante found himself in halfway through his life. Before him was the gateway to hell, with its motto “abandon hope ye who enter here,” suggesting the feeling of hopelessness Tigran invests in his model. But in the upper half of the portrait—like the others, surreally abstract by way of the symmetrical arrangement of the hands and feet in the lower area, the arms and legs in the upper area—she is a heavenly “dream girl,” as the transparent clouds that veil her suggest. Her invisible head is high in the sky—she’s beyond reach, as a goddess is, however much she may reach to the earth, that is, however “earthy” she may be. Has the light that emanates from her body burnt the forest into the desolate wasteland we see in the lower half of the portrait? Once again, Tigran allegorizes his divided consciousness of her by way of her divided appearance. The clouds themselves are divided into a thick lower layer and thin upper layer: opposites are everywhere in Tigran’s portraits of his model. In another portrait—a tondo, like several others—we see only her hands, holding a knife and fork, forming a cross, suggestive of “cutting” suffering. They appear above a white plate with no food on it, suggesting the emptiness the portraitist feels. At the same time, the light that emanates from the plate, and its curvature, suggests that it symbolizes a halo, however broken. Tigran is a master at conveying the auratic emptiness that comes with lost love and the feeling of abandonment.

I think that in the end Tigran’s portraits are about despair and the sense of self estrangement as well as the sense of the strangeness of the Other it brings with it. Nowhere is this feeling of despair more clearly and conspicuously conveyed than in Tigran’s portrait of an elderly Armenian woman hiding her face in her hands. She is no longer recognizable to herself, as it were, no longer wants to see her face in the mirror, for it will only compound—double—the despair she feels.Her black dress is streaked with white lines that resemble the tangle of trees—the bramble—in the portrait in which the young model is half heavenly dream girl, half bewitching devil. Tigran himself is Armenian, a stranger in the strange land of America, a man from a small country living in the big city of New York. Has the American idea that “big is better” led him to make superbig portraits? In part, perhaps, but they reflect the bigness of his heart—the heartfelt intensity of his realism—the heartfelt intensity of the deeply unhappy, painfully suffering old Armenian woman. She is a kind of mother figure—certainly compared to the attractive young model—and Tigran identifies with her, both as a symbol of his Motherland Armenia and as an inconsolably suffering human being. She has been permanently damaged by life, and so has he. In his portrait of the elderly Armenian woman the suffering implicit in his fixation on his beautiful young woman comes out into the open. They were all along about the portraitist—about Tigran—as Dostoievski said a convincing portrait always is. The beauty of his young female model is the mask for his suffering; in the portrait of the old female woman—perhaps the unhappy woman the young model will become when Tigran is no longer painting her portrait, no longer with her—he takes off the mask to show his suffering. The “strangeness in the proportions of beauty”—a strangeness emphasized, even exaggerated by the operation Tigran carries out on it, his distortion of its beauty by surgically cutting it in two, a fatal blow that ruins it—is the sign of the suffering implicit in it. He makes it clear that the seductiveness of beauty is a big lie. Beauty is never as “excellent” or perfect as it seems to be at first glance. Tigran’s portraits are brilliantly executed, a synthesis of what has been called clinical realism and existential realism, and as such scientifically objective and profoundly humanist. More directly to the point, they aesthetically convey the enigma of the eternal feminine and, at the same time, show a certain understanding of her, the understanding that comes from penetrating her being by dissecting her. Indeed, he even pares her to the bone, as the bones evident in the fingers on her recurrent hands suggest.

all images and information courtesy of the artist