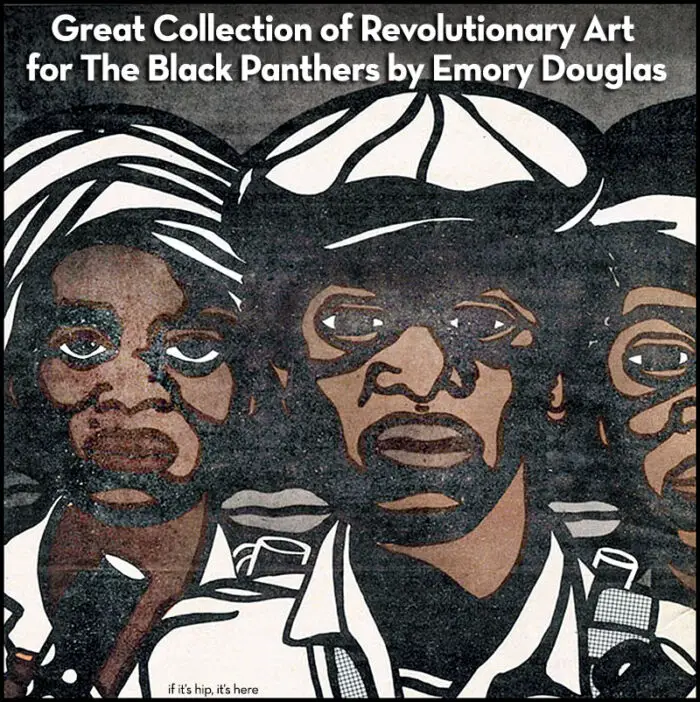

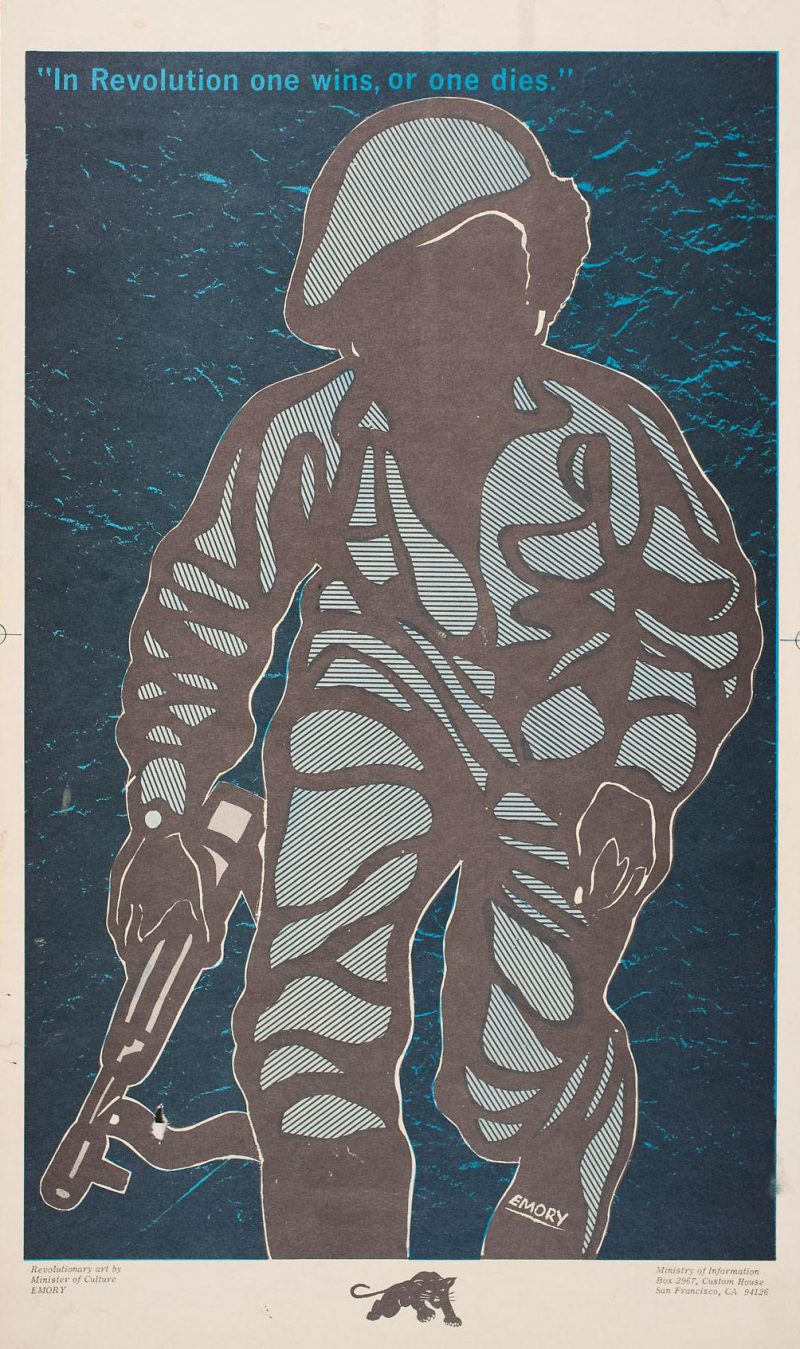

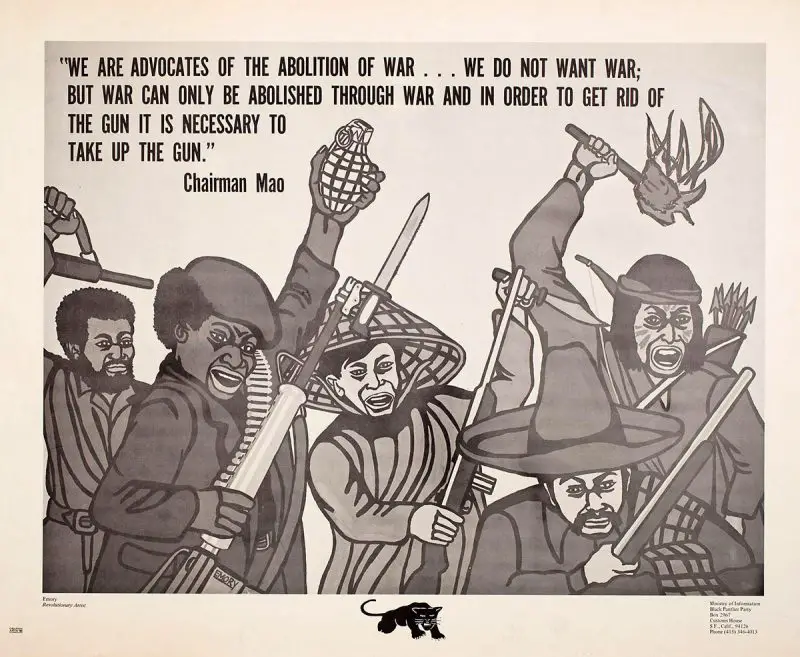

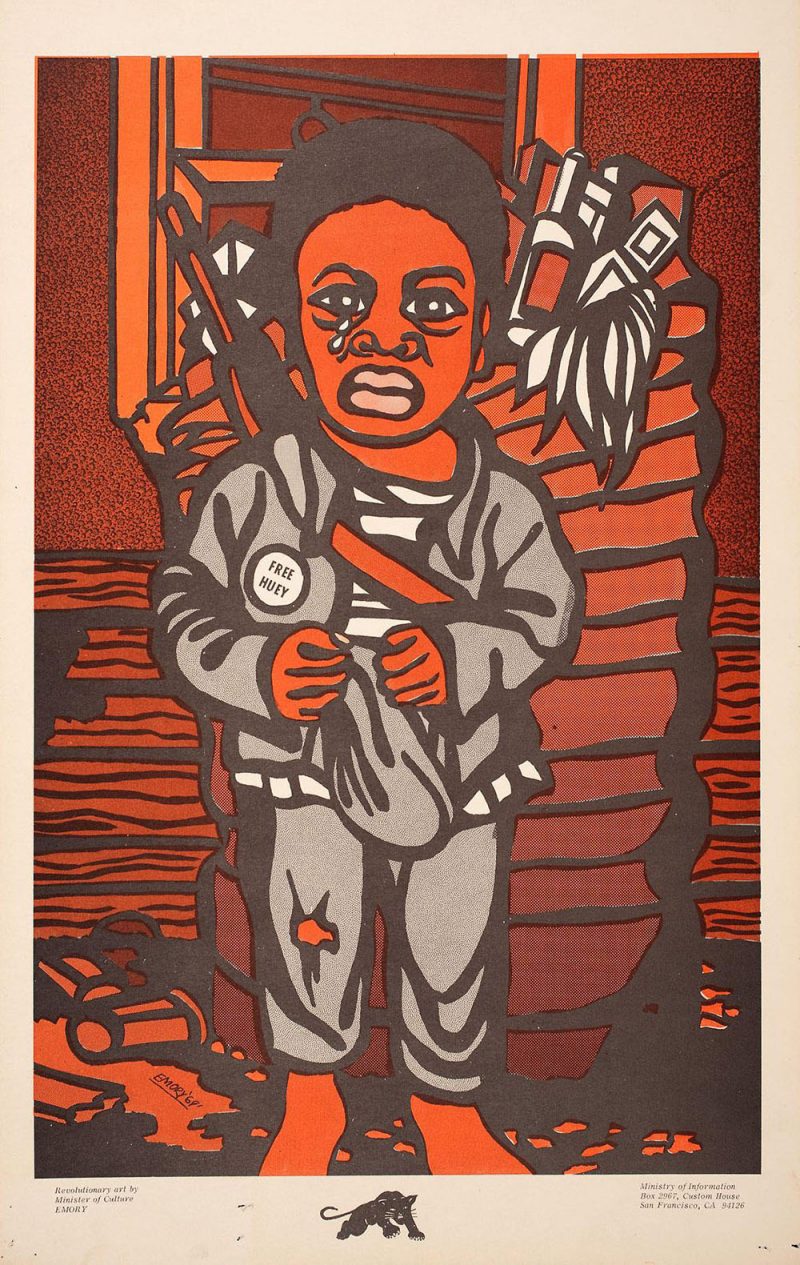

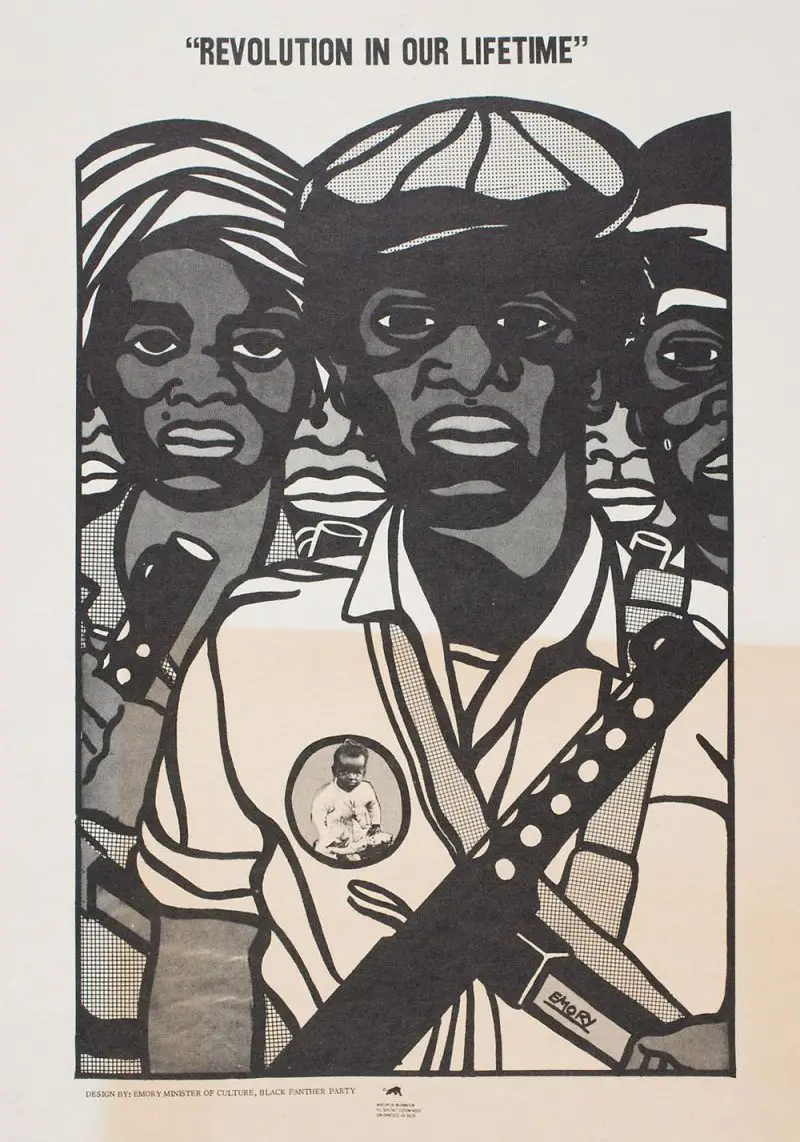

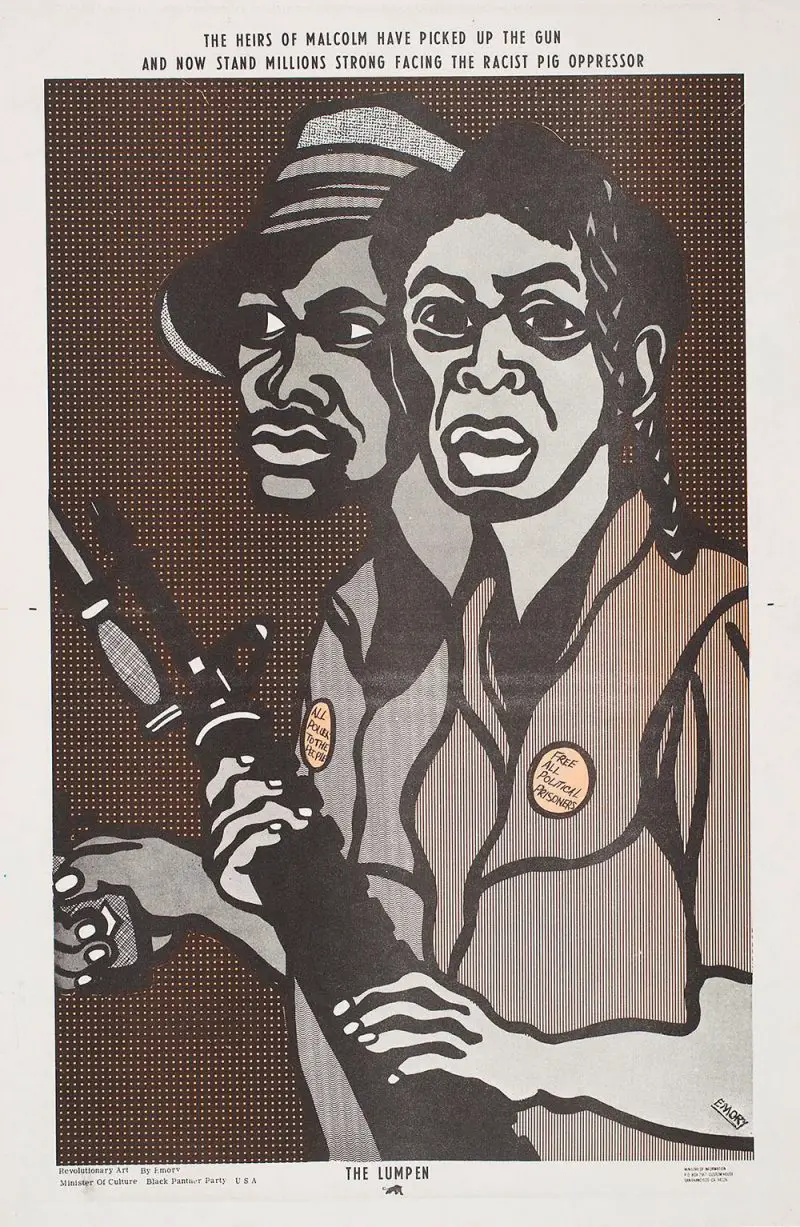

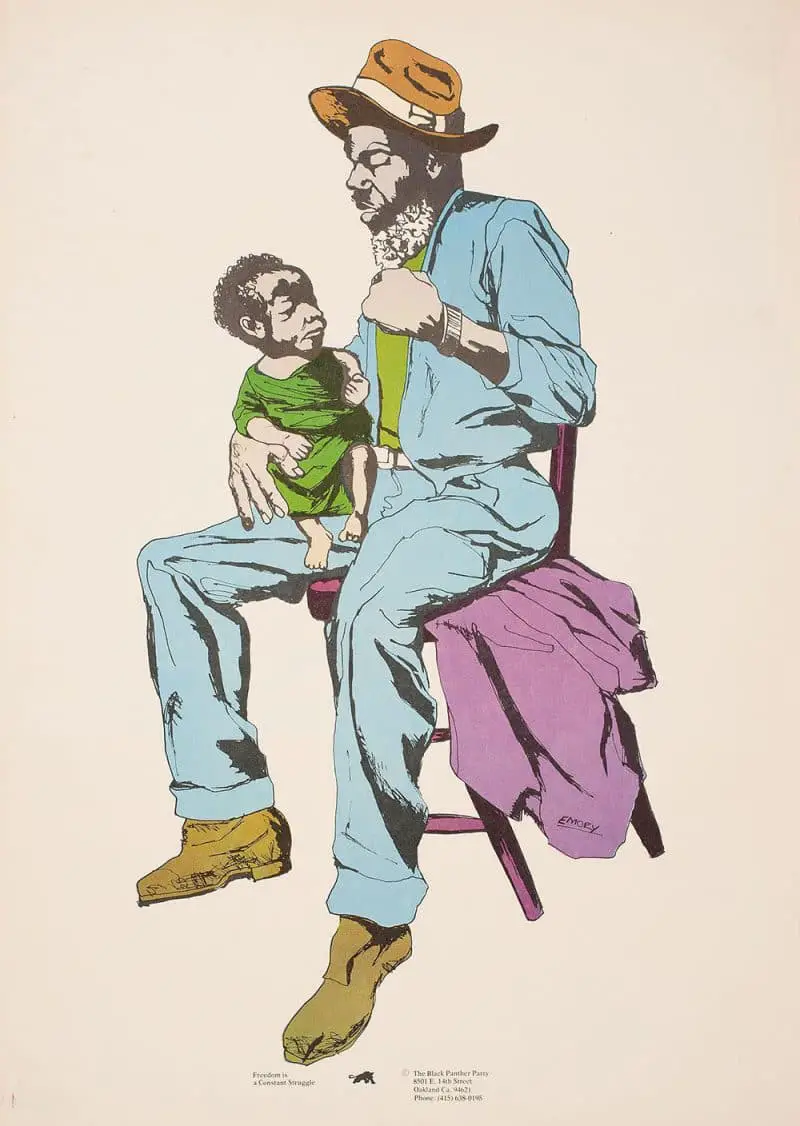

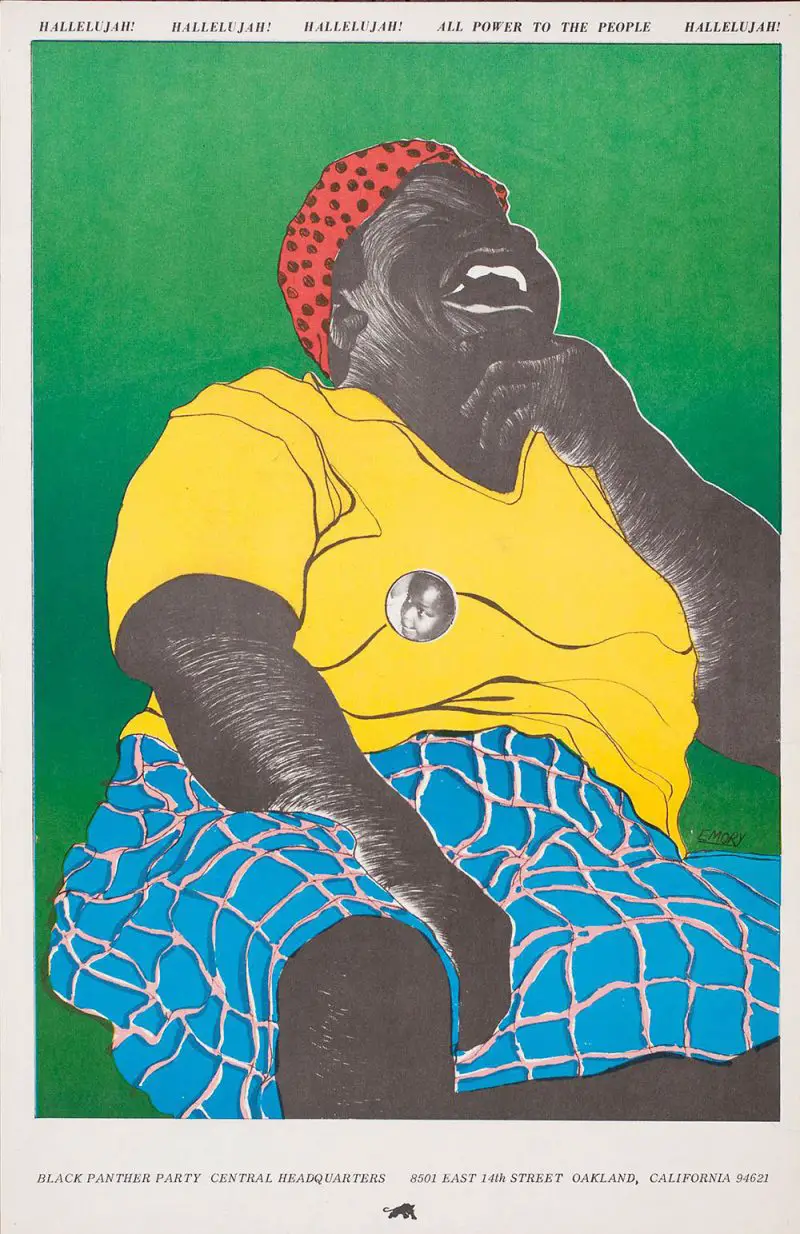

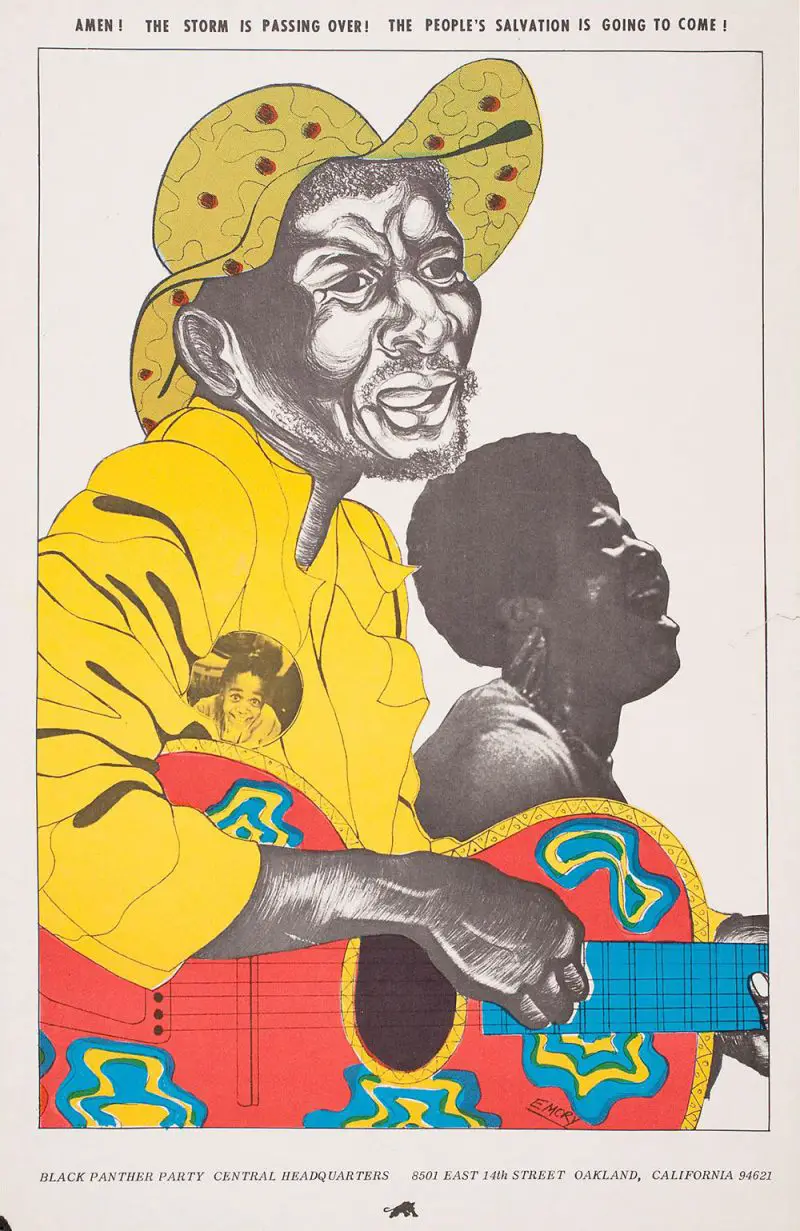

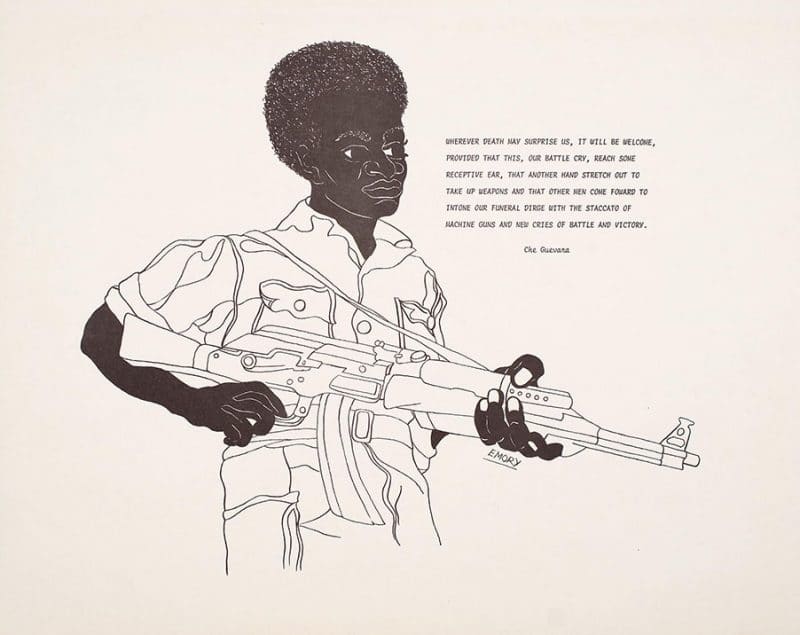

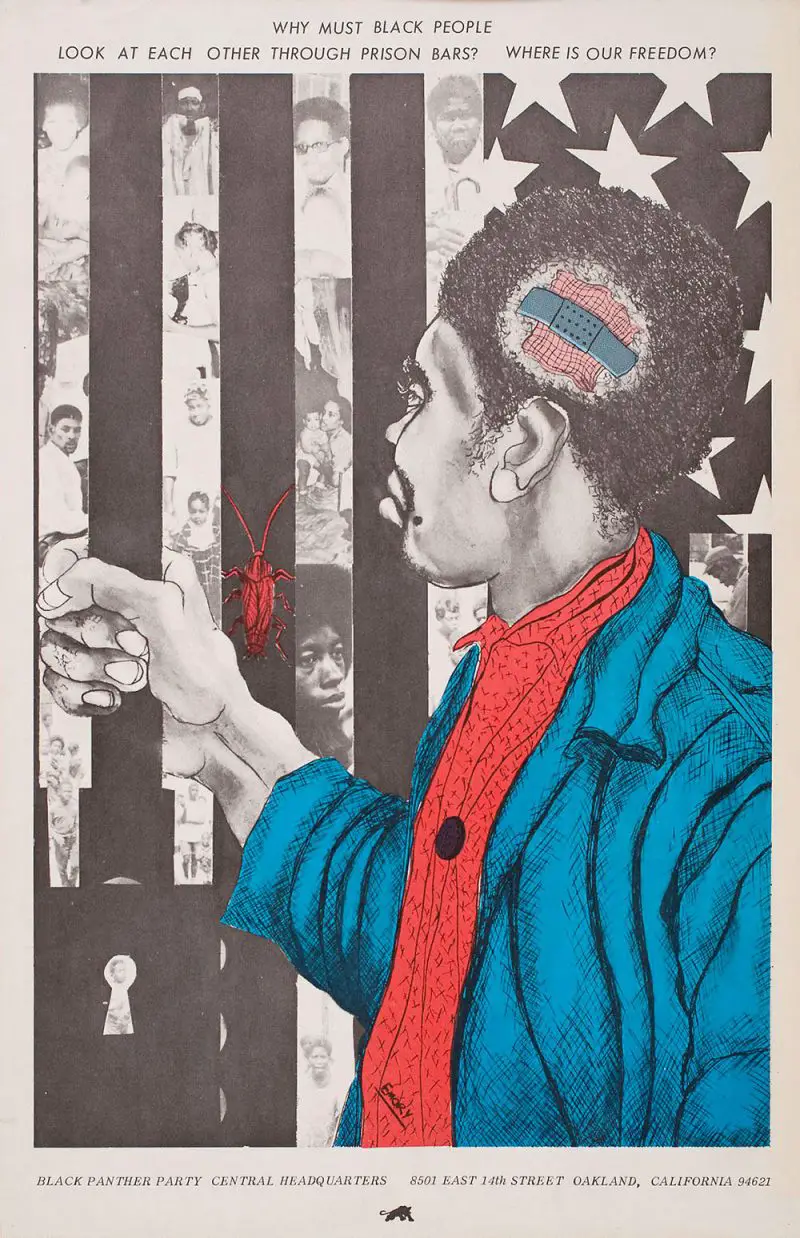

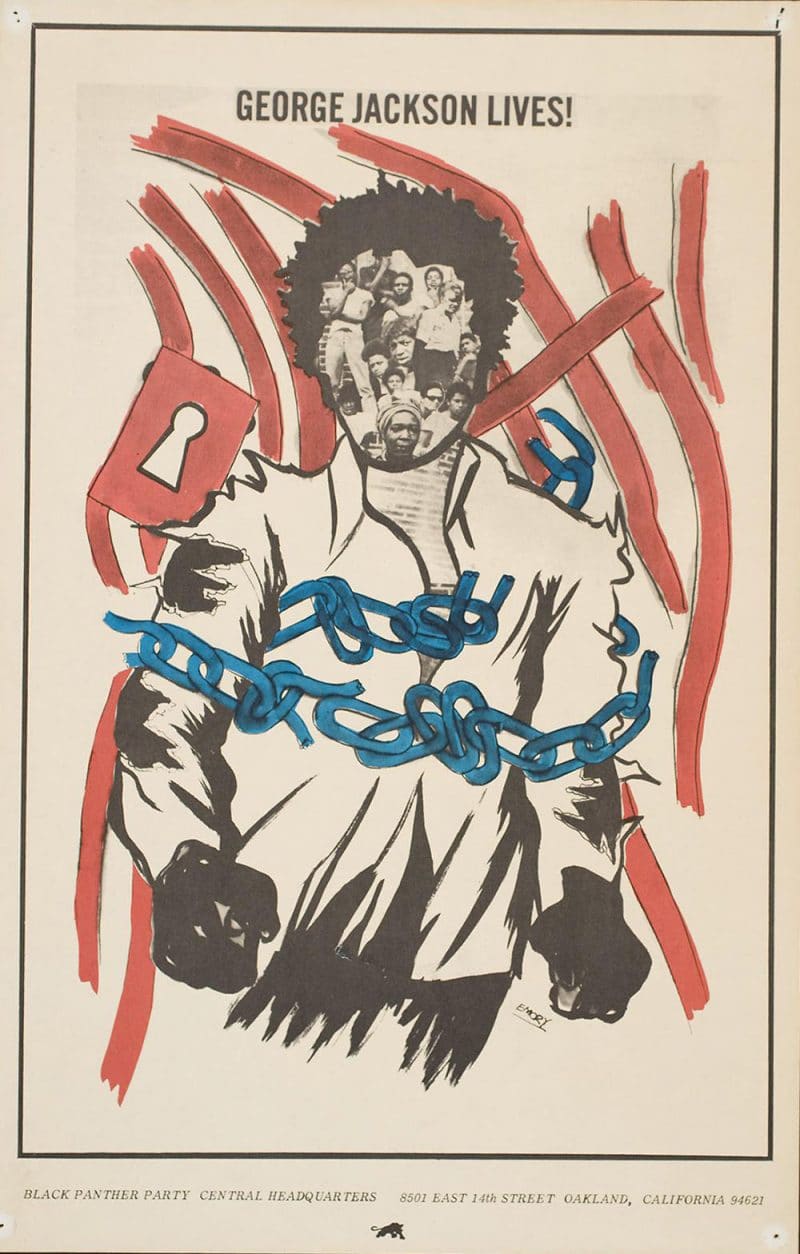

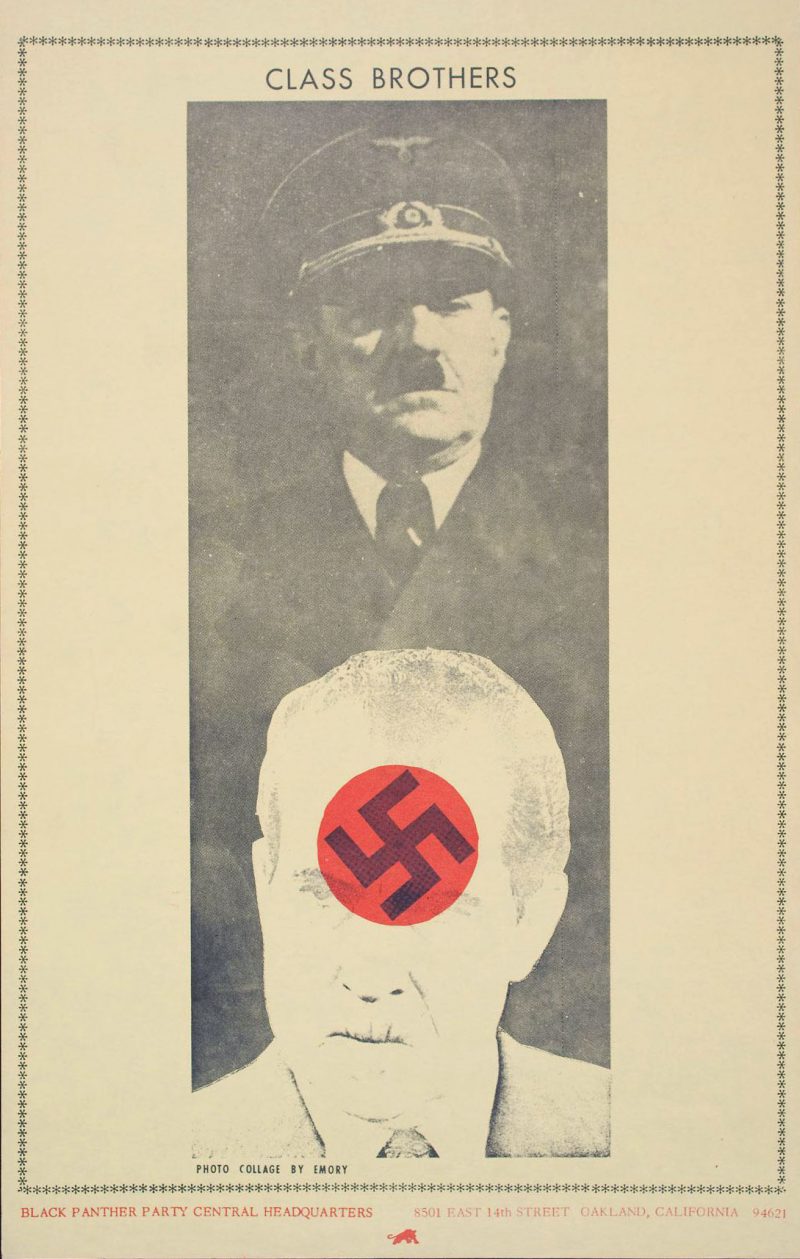

Graphic designer Emory Douglas is best known for his inspirational and historically important revolutionary artwork created as the Minister of Culture for The Black Panthers from 1967-1980.

Emory Douglas Revolutionary Art For The Black Panthers

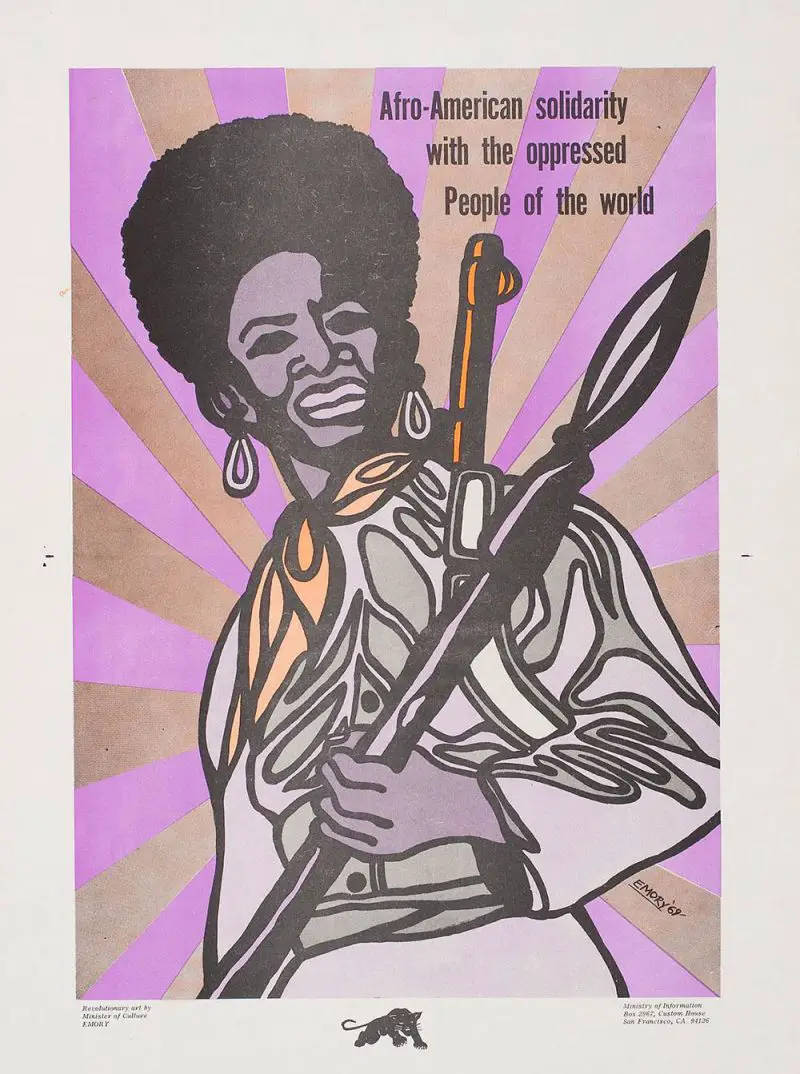

Inspiring the fight for freedom and liberation, his poster and editorial art have been recognized across the globe with several awards for their fearless and powerful use of graphic design and Black Power aesthetic.

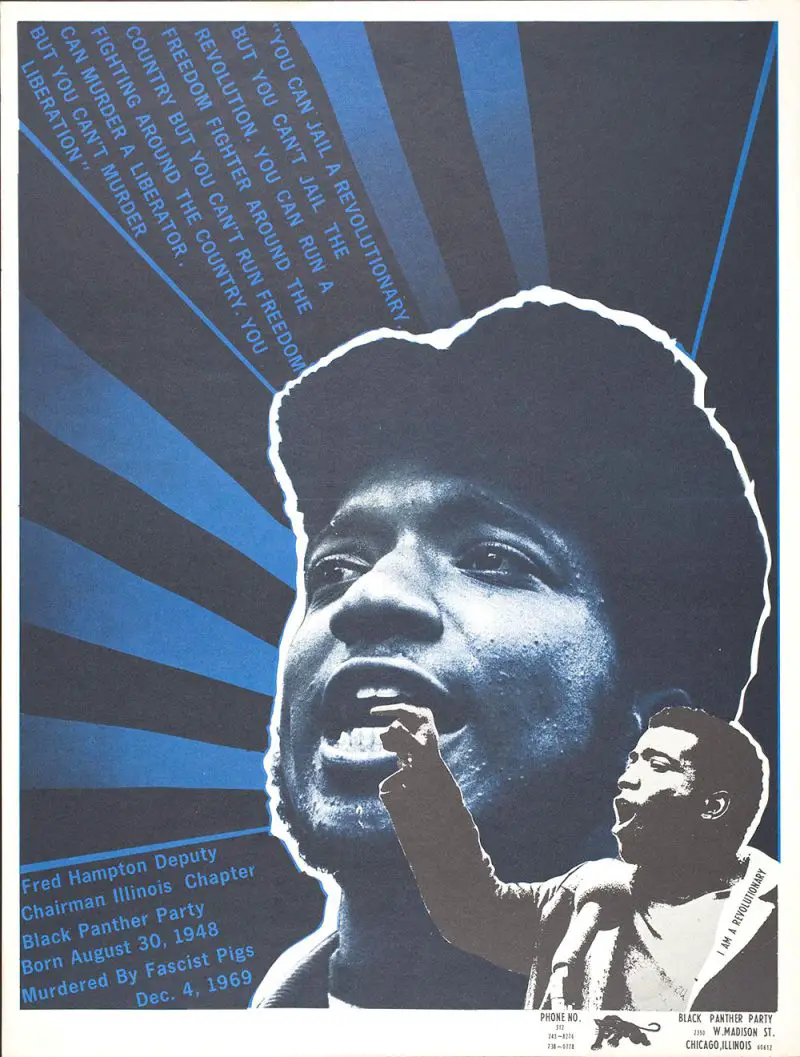

It was in 1967 that Douglas met Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale —founders of the then newly formed Black Panther Party— during a meeting at Eldridge Cleaver’s apartment in Oakland. The impetus for the founding of the party, originally dubbed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was the assassination of black nationalist Malcolm X and the San Francisco Police killing of an unarmed black teen named Matthew Johnson. The Black Panthers’ early activities primarily involved monitoring police activities in black communities in Oakland and other cities.

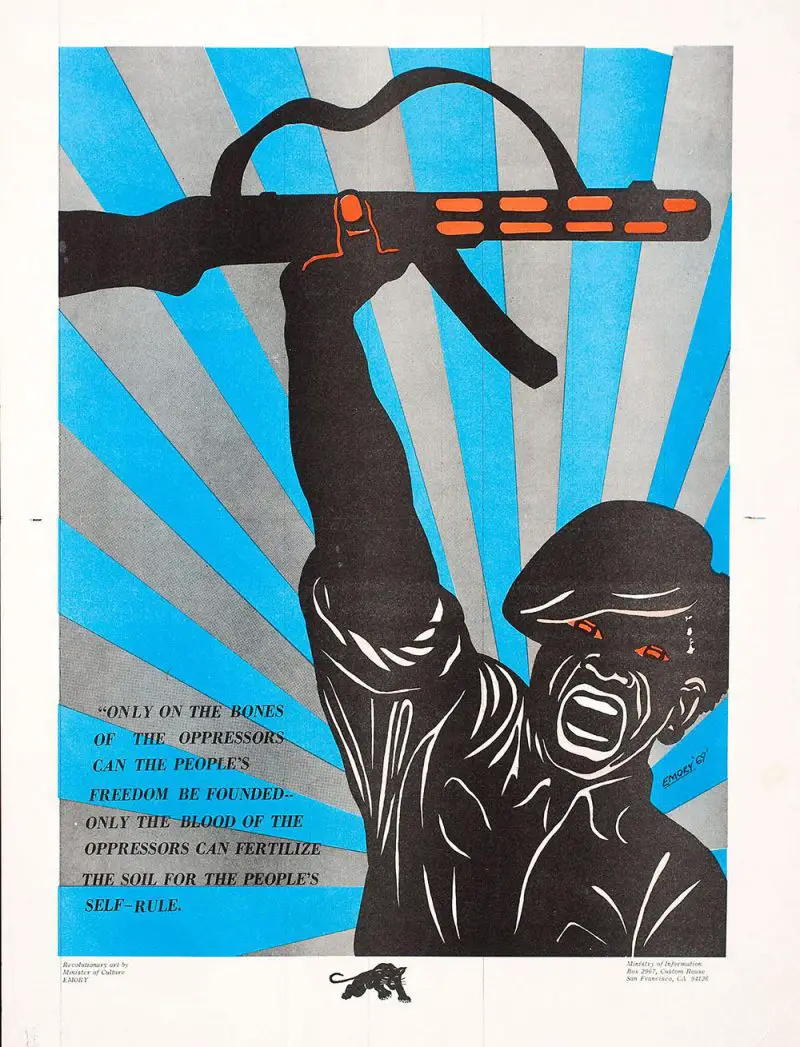

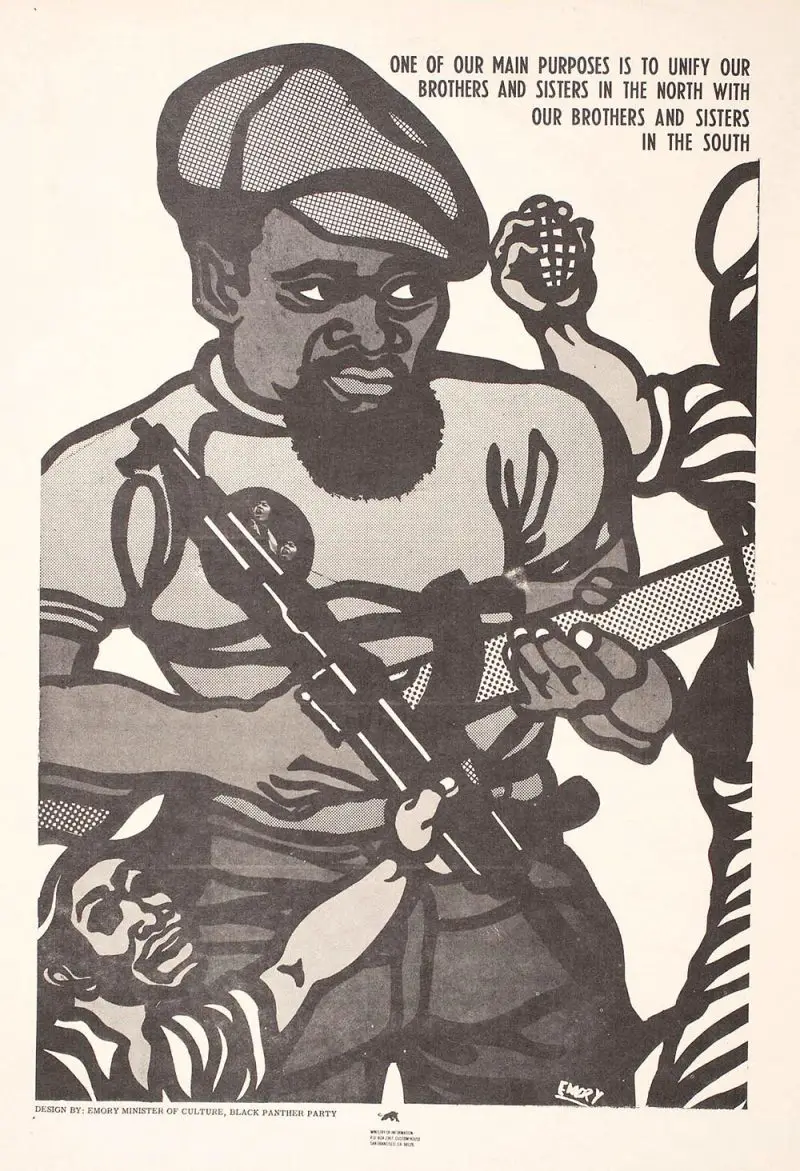

One look at Douglas’ work and the party wanted his vision and skills for its official newspaper – and he was keen to join them. He became the Black Panther Party’s visual voice for the struggle against racism, oppression, and social injustice. Responsible for developing the activist group’s brand, he created heavily-militant propaganda campaign art for the party’s newspaper in hopes to attract new members. Several of the pieces quoted Marxist and Communist ideologies. The newspaper quickly became one of the most popular black newspapers with circulation eventually reaching the 200,000s.

Because of the limited tools at his disposal, Emory used two-color offset printing for the newspaper (which cost 25 cents at the time) and posters. Douglas’ guerrilla graphics emboldened the Black Community and made it possible for many to consider defiance as an alternative to victimization.

As the revolutionary artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panthers from 1967 to the early 1980s, Douglas and his fellow party members were targeted with acts of sabotage by the FBI. According to a congressional report, those acts included spraying production equipment with synthetic fecal scents, ransacking offices, and destroying shipments of newspapers that featured Douglas’ controversial graphics.

Luckily for all of us, the Oakland Museum of Contemporary Art in California has an archive of Emory’s work and many of which are not the ones widely circulated on the web.

A special thanks to The Oakland Museum of Contemporary Art for the images.